Two hundred years ago, almost ninety wagon train emigrants were unable to cross the Sierra Nevada before winter, and almost one-half of them died. The Donner Party was the most famous tragedy in the history of the westward migration.

Their story should be a warning for all those who plan to bug out when SHTF without having a few things already available there. The world has changed, the lessons to learn from their ordeal still remain.

This is a story that every prepper should know. Read it below and think about the mistakes that have been made. Repeating them will kill you.

The 1800s was a century of true survival. The pioneers that crossed the Great Plains and followed the trails out west had a tough journey across lands that we now know to be covered in civilized farmland and crisscrossed by seemingly endless highways.

Pioneer families traveled in wagon trains across the rough, unforgiving terrain. Many travelers were farmers who already had their own supplies, but many had to buy supply kits. Once people got going on the trails, they often found themselves abandoning anything that wasn’t essential so they could lighten the load and make the trip easier.

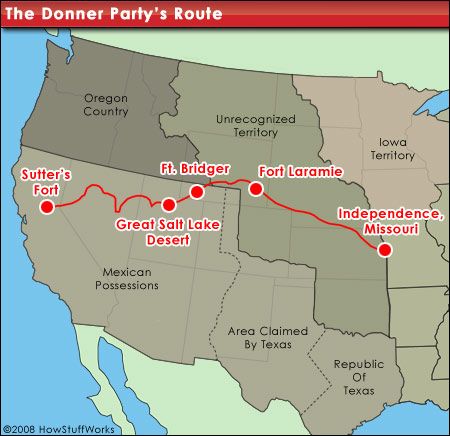

The two most popular trails on the trip west were the Oregon Trail and the California Trail, but then a new route that left the Oregon Trail at Fort Bridger and crossed the Great Salt Lake Desert before joining the California Trail at Humboldt was created.

One famous family that made the journey was the Donner family and a handful of others. They chose to the new route, called the Hastings Cut-off, even though many of whom they were travelling with chose the well-established route through Fort Hall to the north.

This new route had never truly been tested and it ended up slowing down the Donner Party, causing them much hardship and resulting in a devastating journey that stranded them in the Sierra Nevada during the winter of 1846-47.

The Story of the Donner Party

Sometimes known as the Donner-Reed Party, the emigration west was initiated by James Frasier Reed, a business man looking forward to the promise of the west.

He prepared to move his family west in great style. Also in the same wagon train from Illinois was the Donner family, which consisted of the brothers George and Jacob Donner and their families.

The Donner Party left Illinois the very same day Lansford Hastings left California to travel east along his new route and test it out.

The Donner party arrived in Fort Laramie on June 27, 1846, which was only a week behind schedule.

Here, James Reed met an old friend, James Clyman, who had ridden the Hastings Cut-off east with Lansford Hastings. Clyman warned Reed not to take the Hastings Cut-off because the wagons would not get through easily and they would have to deal with the desert and the Sierra Nevada. Reed would later disregard this warning.

The Fatal Decision

On July 19, the party had reached Little Sandy River. They had previously received a letter from Lansford Hastings letting them know that he would personally meet them in Fort Bridger and guide them along the Hastings Cut-off.

At Little Sandy River the larger portion of the original party continued on the established route west and a smaller group, what would become known as the Donner Party, carried on along the Hastings Cut-off.

On the advice of Hastings, the Donner Party crossed the Great Salt Lake Desert, a journey that would be in large part responsible for the future suffering of the group. They had already been slowed down forging a new path through the Wasatch Mountains.

Then they got bogged down in the desert because the desert sands were wet, not dry like Hastings had assumed. A trek they thought would take two days took five days. By the end of it, their supply of water was severely depleted, their food supplies were too low to complete the remainder of the journey, and they lost 32 oxen between them.

Once the desert journey was done, the Donner Party took inventory and found that they did not have enough food and supplies for the remainder of the journey. Two men, William McCutcheon and Charles Stanton, left for Fort Sutter to get supplies and bring them back to the party.

In the meantime, the Donner Party carried on around the Ruby Mountains in Nevada and along the Humboldt River. It was at this point, when resentment of Hastings and Reed began to grow, that tempers began to flare.

At Iron Point, on October 5, two wagons got tangled up. When the owner of one of the wagons, John Snyder, began to whip his team of oxen, James Reed stepped in to stop him.

When Reed intervened, Snyder turned the whip on him. Reed retaliated by fatally plunging a knife under Snyder’s collarbone. That evening the witnesses gathered to discuss what was to be done; United States laws were not applicable west of the states and wagon trains often dispensed their own justice.

Snyder had been seen to hit James Reed, and some claimed that he had also hit his wife, but Snyder had been popular and Reed was not.

Finally, the party voted to banish James Reed, who left with another man, Walter Herron, and rode west. His family was to be taken care of by the others. Reed departed alone the next morning, unarmed, but his daughter rode ahead and secretly provided him with a rifle and food.

From this point on, the pack animals began to suffer and people began to struggle. One old man was not able to carry on and was left behind. There was an attack on the party, the Piute Indians shooting poison-tipped arrows and killing 21 of the pack animals.

By the time the party reached the entrance to the Sierra Nevada, they were almost out of food. It was at this time that Charles Stanton, who had gone to Fort Sutter, arrived with two Indian guides and a number of mules carrying beef and flour. William McCutchen, who had travelled with Stanton to Fort Sutter, had fallen ill and remained there, later to meet up with James Reed, who made it to the fort alive.

At some point an axle broke on one of the Donners’ wagons. Jacob and George went into the woods to fashion a replacement. George Donner sliced his hand open while chiseling the wood, but it seemed a superficial wound.

The worst part of the journey for the Donner Party was when they rejoined the California Trail. By leaving slightly behind other travelers and taking so long to traverse the Hastings Cut-off, it was late October by the time the Donner Party made it to Truckee Lake, now known as Donner Lake.

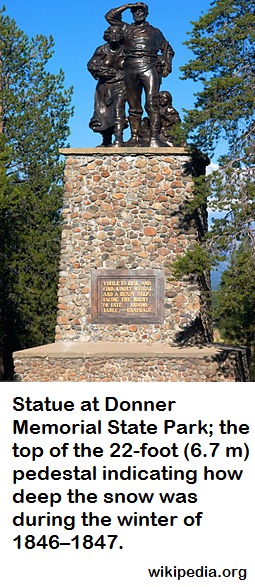

Snow began to fall. They attempted to make it over the pass, but they found 5–10-foot drifts of snow, and were unable to locate the trail in the snow. They turned back for Truckee Lake and within a day all the families were camped there except for the Donners, who were half a day’s journey behind them. Over the next few days, several more attempts were made to breach the pass with their wagons, but all efforts failed.

Some of the party, including the Donners, were held back at Alder Creek, six miles behind the group at Donner Lake.

Three widely separated cabins of pine logs, with dirt floors and poorly constructed flat roofs that leaked when it rained, served as their homes.

The Breens occupied one cabin, the Eddys and Murphys another, and Reeds and Graveses the third.

The families used canvas or oxhide to patch the faulty roofs. The cabins had no windows or doors, only large holes to allow entry.

By the time the Party made camp, very little food remained from the supplies that Stanton had brought back from Sutter’s Fort. The oxen began to die and their carcasses were frozen and stacked.

The pioneers were unfamiliar with catching lake trout. Eddy, the most experienced hunter, killed a bear, but had little luck after that.

That brutal winter saw the people trapped in the mountains eating their remaining provisions, their pack animals and dogs, soups made out of hides and blankets, and finally the members of the party who died.

Cannibalism is something many did not wish to discuss, but there are many accounts of it happening during this awful journey.

Escape and Rescue Attempts

The Donner Party did attempt to escape their wintery death sentence, but the Sierra Pass was impassable. Five feet of snow fell shortly after they reached the pass and numerous attempts were made to get through, but to no avail.

There was one cabin at Donner Lake and they built two more large ones and some smaller ones to shelter the 59 people that had made it that far. By mid-December, the party realized they needed to take action before they were all dead.

Five men, nine women, and one child left the camp on snowshoes. They had little food and were already starving. After six days they were completely without food and by the end of the journey two men and five women had made it through, cannibalizing the others as they traveled through the pass. These survivors managed to tell people living close by about the trapped Donner Party.

In all there were four rescue parties sent out to help the survivors at Donner Lake. The first rescue party left on February 5 and the second, headed up by James Reed, left on February 19. When the first rescue party reached the camp at Donner Lake, there were only 48 people left alive.

They managed to bring 23 of those people out and brought a meager amount of food for those who remained. The first rescue party met up with the second as they made their way through the pass and James Reed was reunited with his family.

The second, third, and fourth rescue parties arrived over a period of two months. Each party that arrived found fewer people alive and they also found evidence of cannibalism. The final member of the Donner Party to arrive at Fort Sutter alive was Louis Keseberg, who made it there on April 29.

Lessons to Learn for Survival

Video first seen on ajvaughan3 Documentary Films.

The Donner family story is one that has long been considered one of the strangest and most tragic crossings in the pioneering history of the United States.

Even though in the U.S. today life is very different from the days of the pioneers, there are many people who prepare for bad times and try to ensure they have the proper equipment, tools, and skills to survive in any setting.

The situation that befell the Donner Party and the struggle they went through is a lesson for anyone who is preparing to survive any post-collapse conditions, including living in the bush for an extended period of time and/or migrating from one geographical area to another.

The reality is, if a disaster of a significant size were to occur, many people would not survive.

The Donner Party learned that lesson the hard way. While knowing what they went through will not change the conditions of a post-collapse society, perhaps the experiences of the Donner Party can serve as lessons to help those who are planning to survive any hard times to come.

Click on the banner below to find out more about what these pioneers took with them in their journey, and the lessons that this story provides for your survival!

This article has been written by Claude Davis, the author of the “The Lost Ways” book.

terrydp | May 6, 2016

|

Great read. I frequently think of the Donner party when a disaster occurs in the world, and I know I can’t be the only one. I’ve read more than one book based on their story, the first when I was about 10 years old (as an avid reader, I’d read anything I could get my hands on). They were in such a scary situation, it got me thinking about prevention even as a child. Boy, did I have an imagination! Now, I think mostly in terms of prevention/protection for my children and grands, knowing I may be the only one standing between them and something like the Donner party faced (none of my children, nor my spouse think beyond today). The story scares me to this day, and prompts me to prepping action even when I don’t feel like it.

rENEE | May 6, 2016

|

My Great-Great Grandpa was in the wagon trail!! Franklin Graves.

Pingback:Survival Lessons From The Pioneers: The Donner Party | NewZSentinel | May 9, 2016

|

Marc White | May 30, 2016

|

Great post. The Reverent reminded me a little bit of this story, or perhaps vice versa. I’m surprised why more movies haven’t been made about early pioneers. Hmmmm… movie idea anyone?